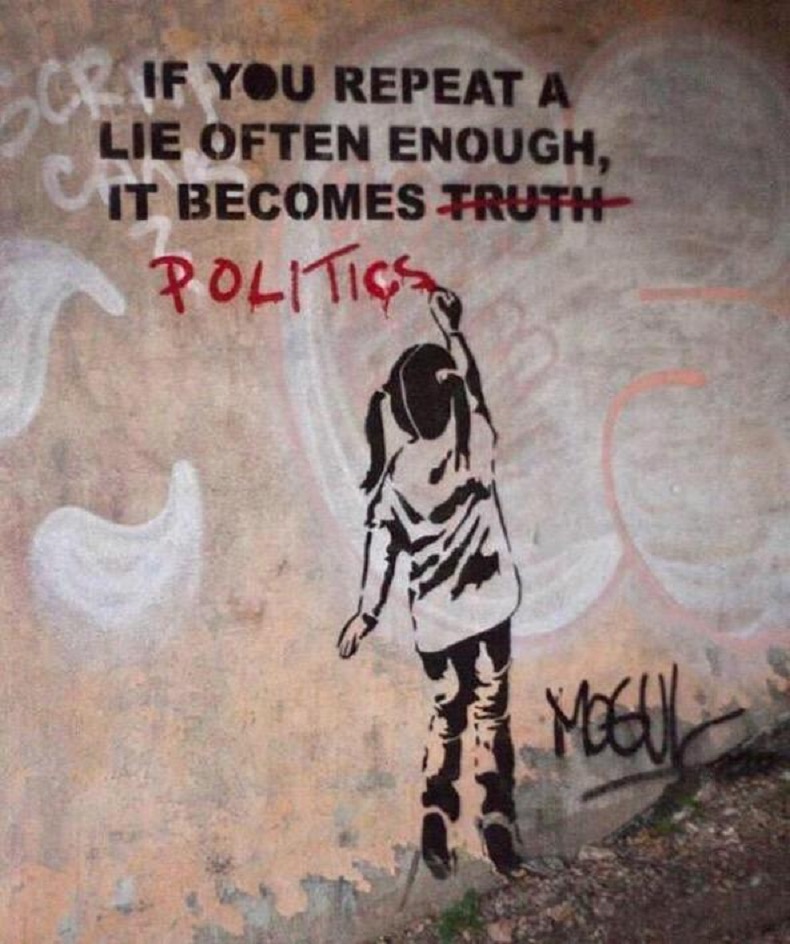

Dramatic tales become effective tools for gaining authoritarian power in modern representative democracies, because of their compelling power.

Populism is the term for an ideology, strategy or form of communication that appeals to “the people”, as opposed to “the elite”. The most effective way to talk directly to people and spark public interest is spreading stories that stir emotion and urgency.

Propaganda means the spreading of an ideology, belief or doctrine. Right-wing populist propaganda uses different types of means from mainstream and left-wing propaganda. I have called the latter “logical rhetoric“, to define the difference.

Logical rhetoric, as we know it from the political mainstream and left, is mainly based on mass publishing of written texts. Exactly described falsifiable facts based on numbers and statistics that can be scrutinised are important. This accuracy is possible because you do not have to remember all the facts and details when they are written down.

Written texts and numbers can be saved, revisited, and shared over time. Falsifiable data like statistics is often preferred in political decision making. They provide cause to effect explanations, and you can check the numbers and have a better control of the outcome.

Facts can be checked

Falsifiability of the political statements are crucial for securing that information given to the voters can be corrected by criticism. The use of mass distribution of information through the the mass media like newspapers, radio and TV and other publications like scientific works and books and have in common that they are transparent for insight and reality check. Everybody can have access to a newspaper article, or a TV broadcast. If it is false, the content can be falsified and the editorial responsible can be sued. A mass published book will be subject to public critics.

Mainstream and left parties uses more causal explanations based on facts. They attempt to find cause-and-effect explanations on a macro political level. For example, how to solve the housing crisis or the effects of climate change.

Numbers and other measurable facts can also be used by right-wing organisations, but in these cases, often rounded up with dramatic exaggeration. When numbers are used in right wing populism, they are often a part of a narrative with a causal explanation linked to individual moral misconduct by members of a minority.

Fallibilism

Inspired by Karl Popper’s philosophy of critical rationalism, an ideal of democratic discourse is that factual claims must be testable and open to critical examination. Popper suggested that “statements or systems of statements, in order to be ranked as scientific, must be capable of conflicting with possible observations. For instance, the claim “all swans are white” is falsifiable. It is about material truth, and is falsifiable by the possible observation of a single black swan.

The logical requirement of falsifiability from Popper applies not only to scientific claims, but to any claim about material truth. Popper argued that claims made within a democratic debate must be open to falsification. He ment this was an essential condition for democracy.

The arguments used in right wing populism are not falsifiable in the same way as the arguments used in logical rhetoric. Use of statements that cannot be falsified, enable the politicians immunise themselves against criticism, with statements like “The policy failed due to sabotage”, or “The media is Fake News “.

Stories are more easily remembered

The language form used Right-wing populism is shaped by its roots in the ancient medium of folk tale; storytelling (narration). Narrative language has a form and content that fit storytelling, originally told verbally from a person to the next. These stories are more dramatic, and less detailed than the texts intended for written publication. This simplicity in structure is because one originally had to remember the stories.

A group of researchers connected to Harvard College has published a study showing that we remember stories much better than statistics. The study document that “as time passes, the effect of information on beliefs generally decays, but this decay is much less pronounced for stories than for statistics. Using recall data, we show that stories are more accurately retrieved from memory than statistics.“

Storytelling can function like a glue, binding a conversation together. It can be entertaining to listen to stories, and this is also one of the reasons why it is so tempting to tell them. We sometimes excuse ourselves for gossiping by sayings like “these are not my words” or “there is no smoke without a fire”. Gossiping about strangers often feels like a guilt-free game, because they are about people from outside our social circle. Gossiping may seem apolitical, but it is important to remember that they are spread as a propaganda tool, especially by the extreme right,

As opposed to facts, dramatic stories are easy to remember. Even if these stories are unrepresentative, they awake great emotional response in the public. These stories hijack our emotions. Dramatic stories trigger strong emotions in us, releasing powerful hormones through our bodies. This emotional response enable the stories to go under the radar and bypass rational scrutiny.

Gossip is inherently important to us

The widespread use of the written language is relatively recent. Before that, we depended on peer to peer delivered information. Gossip was the way information was spread. The mass production of books started in the 16th century. Before this, the vast majority of Europeans were illiterate. Genetically, and probably also mentally, we are not very different from people who lived 40 000 years ago.

This heritage has most likely affected how we perceive, interpret and remember information. When we visit for coffee, we remember dramatic stories about juicy scandals more easily than the small talk and the coffee tableware. Our minds are more tuned into remembering a dramatic story than remembering numbers, statistics and facts… especially if it the story warns against danger.

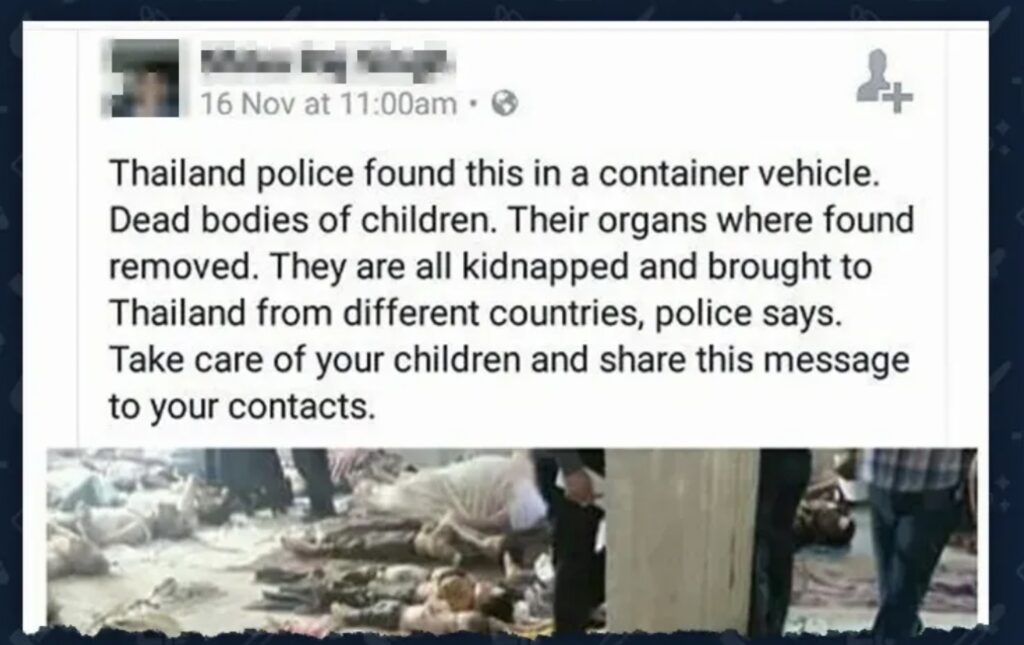

Traditionally these stories are mostly spread in informal fora, like gossip in friends or family groups, or in modern times also through online gossip. Right wing populists today also spread stories on social media on the Internet.

Online stories have the same form and language as the word-of-mouth spread stories. The stories are told from an individual perspective. The perspective is seen from the individuals. It seeks emotional and moral response. It is the drama that is important. Just as the ancient epics framed conflicts as battles between good and evil, right wing populist stories paint minorities, immigrants, or refugees as villains.

We are inherently prone to pay attention to gossip, because gossip has been important for us since the dawn of humanity. Europe lacked a strong centralised state in the pre-modern epoch. Institutions like social welfare, hospitals and an effective police did not exist. People had to rely on friends, family, neighbours, religious congregations and local communities for support.

Robert Dunbar, Professor of Evolutionary Psychology at the University of Liverpool, has proposed the concept of “the gossip factor”, suggesting that gossip played a crucial role in binding social groups among our ancestors together. Social groups like family, friends, neighbourhood charities and religious organisations were probably even more important before public health care and the modern welfare state were developed. Even today, 2/3 of our conversation revolves around social relationships (Dunbar 2004).

You can take a man out of a cave, but you can’t take caveman out of man

- These stories could, if they true, warn us about real and serious threats. Some individuals and groups of individuals, both within and outside a community, engage in actions that pose risks to themselves or others.

- The notion of an external or internal threat can bind a community together.

- They can tell us about the risks of unwanted behaviour. The stories of reckless, immoral or other unwanted actions and the consequences of such, can strengthen the social norms, our unwritten rules for behaviour. The strengthening of norms are important to maintain the social stability, by telling us what acts are wanted, and what is unwanted or dangerous behaviour.

- Gossip stories defines social norms, by telling us what to do and not to do in groups of people, by example.

- Talk in a community also mark social norms by sanctioning unwanted behaviour. The talk in a group of people can be a very powerful sanction, for instance by ousting somebody from the community after a scandal.

One of the negative sides is that ousting can be psychologically damaging for the individuals who are frozen out. It could also lead into stereotyping and xenophobia when the narrative in question forms a bias of an ethnical, sexual, political or religious minority, or about some other out-group. One of the negative sides is that ousting can be psychologically damaging for the individuals who are frozen out.

When the story in question forms bias of an ethnical, sexual, political or religious minority, or about some other out-group, it could lead to stereotyping and xenophobia. Stereotypes are generalisations that assume all members of a group or category share the same behaviour. This can lead us to judge other people before we have even met them.

Right extreme populism makes makeshift politics

While logical analysis is slow to make and difficult to spread, dramatic narratives are fast and easy to make, remember and spread. Right-wing populists exploit this to position themselves in a challenging position to the establishment. Yet, these stories provide a poor foundation for sound policy-making.

The storytelling form makes the content less accurate than you would find in logical rhetoric, that is based on written tradition. This also means that there is less empirical accountability. The extreme right focus more on criticising other politicians and their alleged faults, than on formulating their own political programmes.

Urban legends (wandering stories)

The sensation and the drama is important for making an urban legend successful. Psychology researcher Joe Stubbersfield states that stories about people are more interesting to us than stories about the physical environment. Firstly, he states, people are attracted to stories about threats to survival and social relations. They were also more likely to pass both these categories of stories on. Secondly, urban legends that contain social information, like the cybersex legend, or combined social information with information about a survival threat, such as the terrible baby crying legend, were far more easily remembered than those only carrying survival information, such as the spider in the hairdo legend.

Facts can kill a story

Any journalist knows that checking the facts to rigorously can kill a story. A thorough fact check often reveals that there was no story, just hear-say. Also, if you describe to much of the background of the characters, you also risk to kill the drama in the story. It is the drama created by the moral conduct of the perpetrators that create many stories. If the perpetrator fell down a staircase as a child and injured his head permanently, it would take some of the action out of the story, as he was no longer morally responsible.

It was not hard to see who were the bad guys and good guys in old western movies. The characters were stereotypical. The villain is the engine who drives the action of the story forward, which makes the drama and the emotional tension. If you make the characters to complex, you take the drama and the momentum out of the story. The stories are simplified by taking away details, context and nuances.

The urban legends function the same way. The main characters in in urban legends are stereotypes. A villain often does immoral acts against a innocent, unsuspecting and and defenceless victim. The culprit is often someone in an out-group of people, outside of the majority groups social circle and knowledge.

The sensation in itself is often a reason for us spreading a story. It is important that one can identify with the story, that you are deeply engaged and absorbed in the story. Hence the individual perspective. Stories need conflict in order to create drama and, thereby, interest.

There is no fact check in gossip. Urban legends contain little verifiable or falsifiable information or real sources, as they are spread from person to person. Such stories spread no matter if the origin of the story was true or not, according to Klintberg.

Is there a reliable source or is it hearsay ?

The storyteller often places the story in a specifically named place. The source is often a friend of a friend, and often a reliable person like a doctor, police officer or other official. It is according to Klintberg seen as a guarantee that it is true in many peoples eyes if the story has appeared in a newspaper. This shows the level of substance in storytelling.

Although news media sometimes feature urban legends and conspiracy theories, a free press remains essential for public debate, providing voters with reliable information, and upholding democracy. Editorial fact-checking often exposes conspiracy theories, and news media frequently offer critical analysis of those in power.

The editorial control of mass media is like watertight compartments on a ship, that is ment to stop false claims. It is not perfect, and urban legends and other false stories find their way through the gatekept media more often than you should think. It is important to stay critical of media coverage, as some of the outlets have their own political stances, that makes them select or angle the news after a specific perspective.

Unlike unregulated social media, news organisations have editorial accountability and can face legal consequences for spreading misinformation. For example, Fox News paid a $787 million settlement to Dominion Voting Systems to avoid a trial over promoting false claims about the 2020 election, according to Associated Press. In aditittion to the legal risk, a news outlet also risk loosing its credibility if it publishes unverified stories.

It happens some times that urban legends and other misinformation find their way to gatekept media. But it is more seldom that outright conspiracy theories are found there.

Still, the editorial control is a better reality check than gossip stories in private conversations or in social media on the internet, that have no such hindrance.Unlike social media, where misinformation spreads unchecked, traditional media can be held accountable. Right-wing populists often attack mainstream media in general to promote social media platforms, where stories and conspiracy theories thrive without resistance. A research study from MIT found that false stories spread faster than true ones online.

Gossip is not a victimless activity. Klintberg has described how such stories in several cases has led to hostile attitudes towards minorities, immigrants and refugees, like the story of “White slave trade”. It is described in chapter 5 how the old German Nazi party used the same urban legend in their propaganda.

Urban legends used in propaganda interlock together with other tools such as memes in drawings, images, leaflets, movies, TV, radio commentary and texts spread on social media platforms on the Internet. As shown in chapter 12, spreading of peer-to-peer by sharing a story is incredibly efficient. Storytelling is the key element in right-wing populist propaganda, which many of the memes refer to.

Urban legends spread by political actors

The Cybersex legend, the baby crying legend and the spider in the hairdo legend are examples of urban legends. Another example is the story about Haitians in Springfield Ohio eating cats, that was used by the Trump campaign, closely resembles an old story document by Jan Harold Brunvand.

The American folklorist Jan Harold Brunvand documented urban legends from the 1980s, that claimed Asian refugees were consuming pets in areas like Salt Lake City, Utah; Stockton, California; and Fairfax, Virginia, among others. “Evidence was supposedly found in garbage cans, and people had heard about Vietnamese wanting to buy puppies or kittens to use for food”, Brunvand wrote in “The Mexican Pet”.

It is easier for urban legends to be admitted into the mainstream, as it is more socially acceptable to tell urban legends than outright conspiracy theories.

An urban legend that was spread by right wing influencer Chaia Raichik claimed that public schools had installed litter boxes to meet the demands of pupils who identified as cats, according to Southern Poverty Law Center. Politifact and NBC writes that the story has been claimed as true by at least 20 Republican political candidates. The story has also been pushed by influencers Majorie Taylor Greene, Lauren Boebert and Joe Rogan, according to Politifact.

The Statesman writes that the story started with a video where a women made the claim about schools in Midland. The video had more than 91 000 views. It did not help that the story was rebutted as false.

The Bathroom predator or “locker room predator” is an urban legend claiming that that sexual predators will exploit transgender non-discrimination laws to sneak into women’s restrooms Media Matters writes. -“Experts in 12 states — including law enforcement officials, government employees, and advocates for victims of sexual assault — have debunked the right-wing myth calling the myth baseless and “beyond specious.”

The myth has been spread by conservative outlets like Fox News, The Daily Caller, WND, and the Media Research Center, stated by Media Matters.

The psychology researchers Jean E Fox Tree and Mary Susan Weldon have published a study of how urban legends are retold. They say that while legend is generally presented as true by the teller, a rumour is a story presented as if you do not know whether it is true or not.

They found that frightening stories were more often retold. They also found that stories that had been frequently repeated in the past, also had a greater chance of being repeated in the future. They hypothesised that the repetition in itself increased the credibility, importance and scariness, and thereby the likelihood of being retold.

Additionally, they observed that urban legends were more likely to be retold when the teller believed in them. Because, unveiled as false, a retold legend might become an embarrassment to the teller.

Further, a story that was believed by the teller to be of importance, was often retold. Probably because not passing on potentially important or life-saving information would not be risked.

A collection of urban legends are found at www.snopes.com.